You know how it is when you know someone who is intensely irritating. They drive you nuts. But just sometimes, unless they are real monsters, you find that inexplicably you get quite fond of them. Even though they still annoy the hell out of you.

Some books are like that.

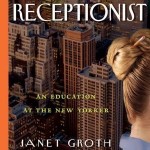

I love The New Yorker. Or rather I love the idea of it. I haven’t read that many issues though I am familiar with the cartoons; it’s one of those magazines that are part of my childhood and growing up. Like Punch. So I was eager to read The Receptionist, to get the lowdown on what life was like in the creative and humorous hotbed that was The New Yorker in the late nineteen fifties and sixties. The era of Madison Avenue and Mad Men.

Founded in 1925, the magazine covers reportage, commentary, essays, fiction, satire, poetry and cartoons. While reviews and events focus on the cultural life of New York City, it is widely read throughout the world. I have to admit, to my shame, that many of the writers mentioned in The Receptionist are unknown to me. Others, though, are old friends and firm favourites. S.J. Perleman, Peter DeVries, Muriel Spark and James Thurber to mention just a handful. So it was with happy anticipation that I settled down to read

My excitement was short lived. The irritation set in from the very first page with what appeared to be an implausible story. A naïve new graduate from the University of Minnesota takes a temporary job with a film director, who immediately invites her to send in her resumė, which he promptly passes on to the famous New Yorker writer E.B. Wright who agrees to interview her. I’m not doubting it happened – things like that do happen. But the name-dropping and the smug self-satisfaction turned me off straight away.

I was eager to read The Receptionist, to get the lowdown on what life was like in the creative and humorous hotbed that was The New Yorker in the late nineteen fifties and sixties. The era of Madison Avenue and Mad Men.

The interview was ‘unprecedented’. Her attitude to the famous writer patronising – ‘I was overwhelmed with a desire to put the poor man at his ease.’ Her statement that ‘anything would be of more interest’ than the typing pool, is arrogant in the extreme. None of this endeared me to the author. However, I decided to battle on. And it was a battle. I read ‘The Receptionist’ on and off for several months; it felt like a very long six months.

There’s something self indulgent about this book, at least the first half of it. Something self-conscious. In many places all it amounts to is names, famous names, trotted out one after another. As I mentioned, most of the names meant nothing to me but that’s hardly the author’s fault. However, I’d have liked to know more about them, I thought that was what I’d get from reading the book. I didn’t in the main. There were some highlights. I had read most of Muriel’s Spark’s work when I was younger and loved it. So a whole chapter devoted to her had me sitting up and taking notice. I found myself thinking, goodness this bit is actually interesting.

If only she had kept it up.

The book’s covers and no less than four pages at the beginning contain glowing reviews from the likes of The Chicago Tribune, The New York Times, The New York Journal of Books, The Washington Post and more. At first my impression was that I had been reading a different book. I don’t understand how The New York Journal of Books, for instance, can refer to “verbal dexterity” when some passages are so muddled I had to read them over and over to make sense of them. And when other sections read like a mushy romantic novel and others are plain silly – “how could I ever go to bed with someone who not only misquoted Coward but could dis the song Ingrid was humming just before she said, “Play it, Sam.”? “ You could be forgiven for thinking that was meant to be either funny or ironic. It isn’t. It’s twee.

For the book’s real pleasure is indeed the self-examination. The dawning self-awareness and the not inconsiderable courage of the author in putting it out there for all to see. It is this honesty and self-knowledge that begin to throw light on the earlier chapters.

To get back to what I said in the beginning. About getting fond of people even though they continue to annoy the hell out of you. That applies to this author, because if ever a book was its author this one is. I’m going to quote two other reviews because they describe the element that endeared the author to me despite everything. The thing that kept me reading fairly consistently from about half way in. Oprah.com said, “Groth … isn’t a woman to give up and, by the end of the book, she finds her own delightful voice, which is the book’s real pleasure.” And The Boston Globe – “A literate, revelatory examination of self.”

I take issue with the ‘literate’ but apart from that those two quotes describe why I didn’t abandon the book half way through. For the book’s real pleasure is indeed the self-examination. The dawning self-awareness and the not inconsiderable courage of the author in putting it out there for all to see. It is this honesty and self-knowledge that begin to throw light on the earlier chapters. To reveal not so much a shallow, self important young girl revelling in her affairs with famous people, but a bright and talented young woman somewhat adrift and needing direction.

Janet Roth was young in an era where men were all powerful and women, on the whole, were wives, housewives, typists or merely decoration. The era brilliantly depicted in the TV series, Mad Men. There were of course a few highly paid and powerful women columnists at the New Yorker in the nineteen fifties and sixties. Writers such as Muriel Spark and Dorothy Parker were also regular contributors. But you can see how a young aspiring writer from the mid-West, with absolutely zero confidence yet abundant feminine charms, could end up spending eighteen years as the receptionist on the eighteenth floor. The writer’s floor. Yet never getting that longed for chance to join them.

Absurdly generous vacation leaves, with pay, plus indulgent working hours also contributed to this extraordinary long and ultimately fruitless employment. However, these conditions also allowed her to take classes and travel widely and all credit to her for keeping up with her studies. She may not have had the confidence or push to get herself the job she wanted. She may have been star struck and wild and self-absorbed, to say the least. But she didn’t give up. She just came at writing a different way. She obtained her Ph.D. in English, became a Fulbright lecturer and Professor Emeritus in English at a New York State university, taught at various other universities and is the author of three books on the literary critic and prolific writer, Edmund Wilson.

So I have to confess I did grow quite fond of her in the end. I certainly admire her courage– her self-analysis is honest an insightful. As to the book itself – it still annoys the hell out of me.